Author: Alida Metcalf

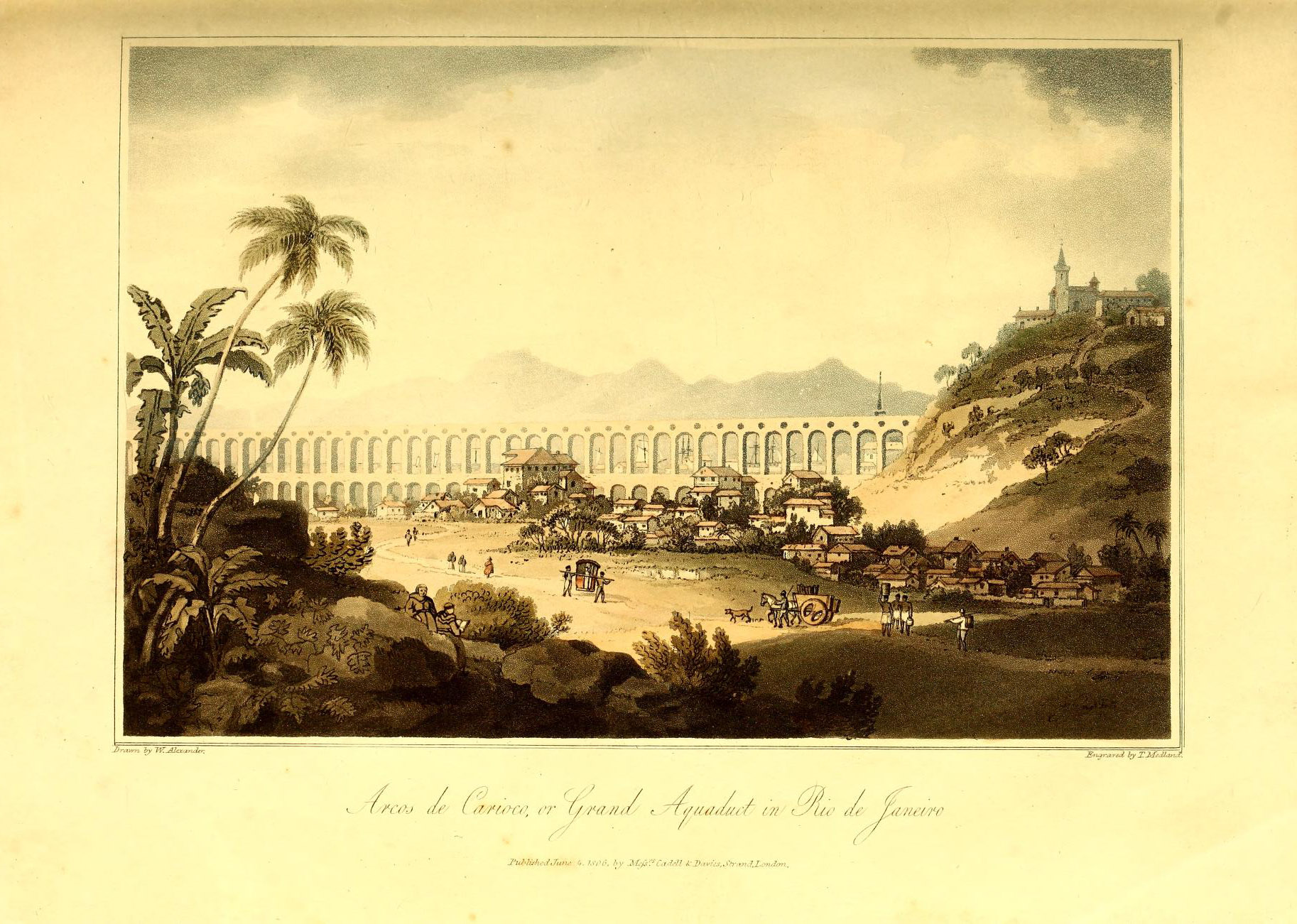

Founded as a fortified outpost in the Portuguese maritime empire with little thought given to future expansion, the city of Rio de Janeiro did not have a reliable source of water until the early eighteenth century. When an aqueduct began to flow in the 1700s, it brought excellent water from the headwaters of the Carioca River, deep in the Tijuca Forest, to the city. European visitors raved about Rio's water, but it was a fragile system that never adequately or equitably supplied water to city residents. The aqueduct depended not only on engineering but also on the forced labor of enslaved water carriers. Today one piece of that aqueduct, the Arcos da Lapa, remains one of the iconic monuments in Rio. Still invisible is the story of the aqueduct, its fountains, and the water carriers who delivered water through the city.

Despite its name, Rio de Janeiro does not lie on a river. The name was initially given to the Guanabara Bay, a large semi-circular oceanic body of salt water. Fresh water rivers and streams flow into the Guanabara Bay, but Rio did not, unlike most cities, grow alongside a river. Instead, Rio unfolded around the salt water bay and access to fresh water has always been problematic. It has always been necessary to engineer fresh water into the city. This began with the building of an expensive aqueduct in colonial times.

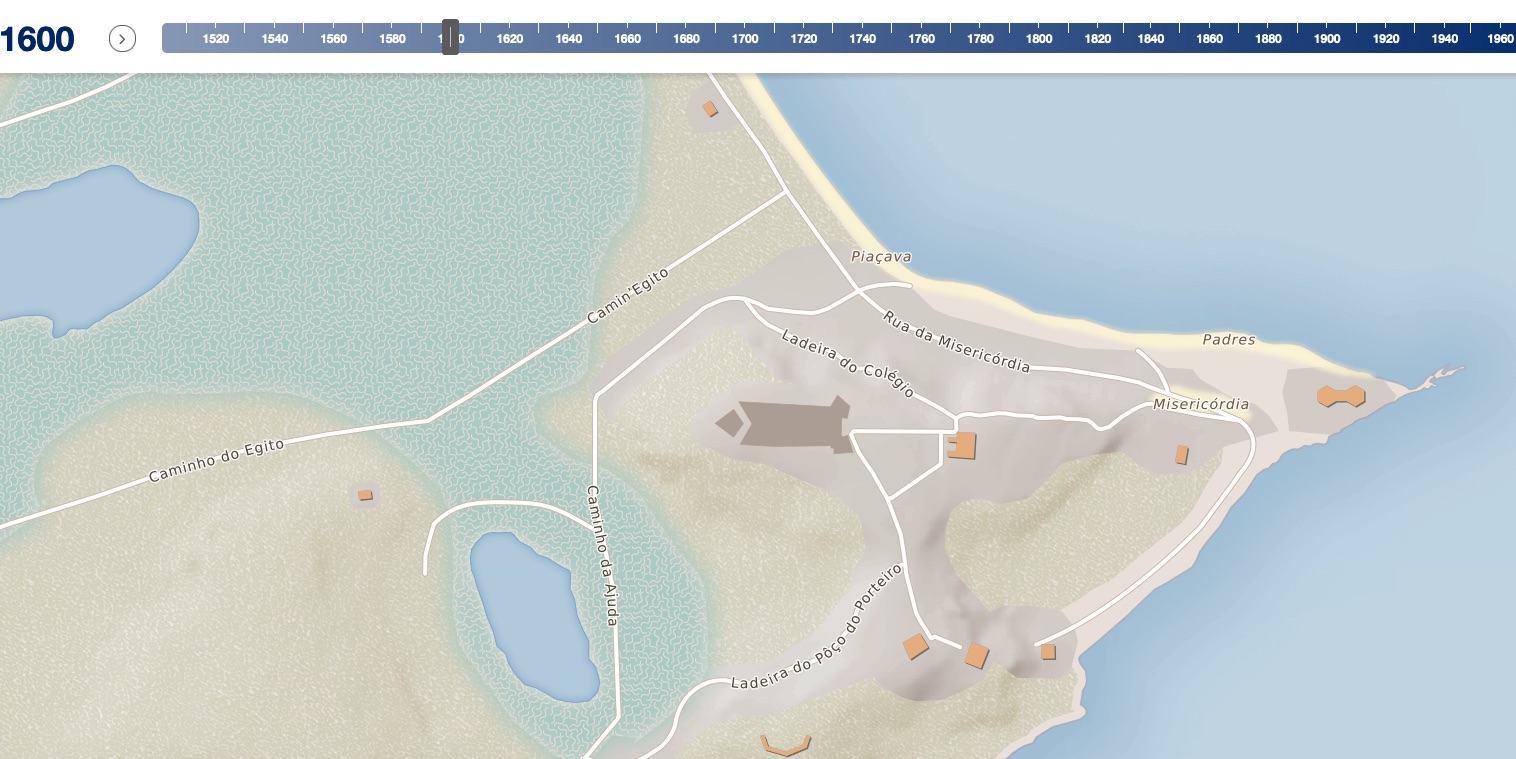

The founding of the city of São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro in 1565 occurred without much thought given to water. Although there were many rivers and streams that flowed into the Guanabara Bay, defense determined where the first settlements were situated. Salvador de Sá chose a protected inlet at the foot of the Pão de Açúcar for his military base. With a small force from São Paulo, he joined his uncle, Mem de Sá, the governor of Brazil, in the attack on the French fort and their Tupinambá allies who lived around the bay. Following the surrender of the French fort and the Tupinambá chiefs, Mem de Sá selected a site high up on a hill well inside the bay. Soon known as the Morro do Castelo (Castle Hill) because of its fort, its location was entirely due to the strategic need to defend against attacks by the Tupinambá or the French.

The Morro do Castelo site offered a commanding view of the Guanabara Bay, especially of its narrow entrance, and its height and steep approach made it easy to defend. Mem de Sá later wrote:

"I chose a place that seemed better for building the city; that location was then a thick forest, full of many huge trees that took a lot of work to fell and clear."

The São Sebastião Fort dominated the Morro do Castelo, and around it lay the Jesuit church, a municipal council house, a jail, royal warehouses, and two-storey houses with tiled roofs for the first residents.

On the Morro do Castelo, water came from local springs and wells. The water was good but barely sufficient for the number of residents. Below the Morro do Castelo, the Rua da Misericordia was one of the earliest streets in Rio, and it fronted the simple anchorage along the bay. When the Benedictines chose the site for their monastery, they selected the top of another hill that overlooked the bay. Here too the monks had good water from springs and wells.

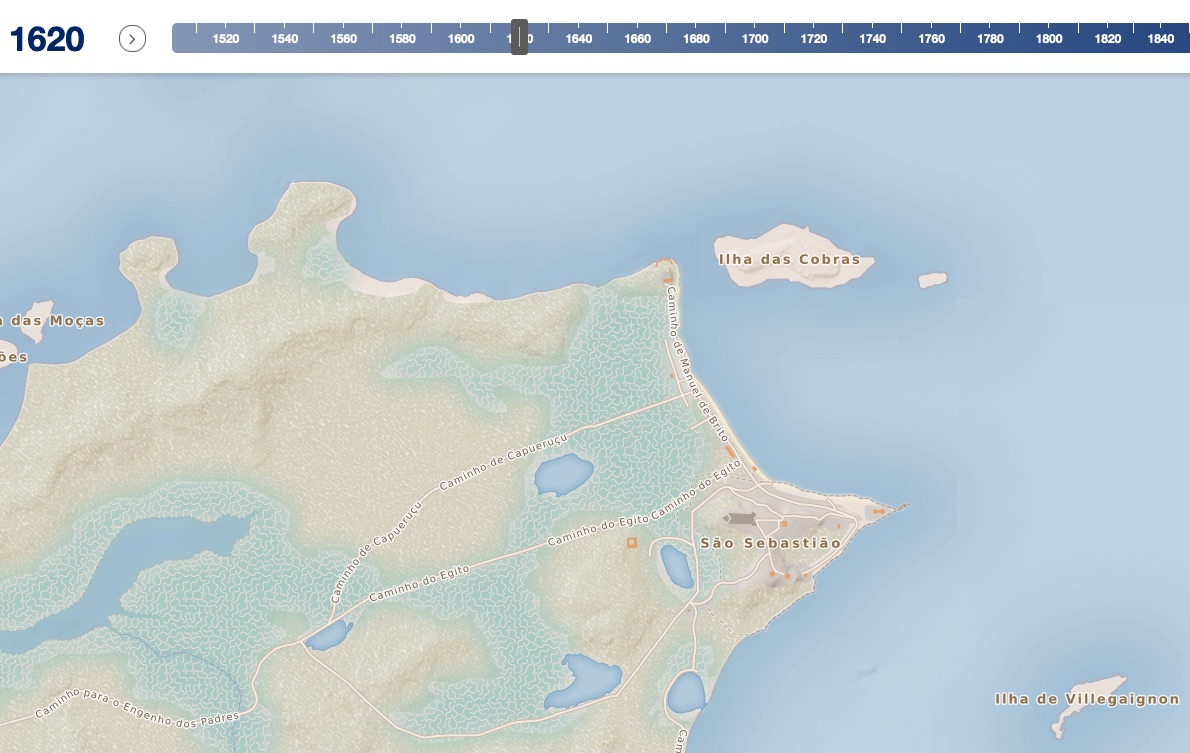

Between the two hills lay a narrow beach and a large mangrove swamp. Lagoons and ponds were other watery environments that hosted many fish and crustaceans, but the water was too salty for drinking. There was no river in this area between the two hills, which were linked by another early street: the Caminho de Manuel de Brito.

Once forts were built around the bay to protect Rio de Janeiro, the residents began to move down from the Morro do Castelo and settle along the Rua da Misericordia and the Caminho de Manuel de Brito. This lower settlement offered easier access to the bay, but the nearest sources of freshwater--the Papa-Couve River and the Carioca River, were both quite far away.

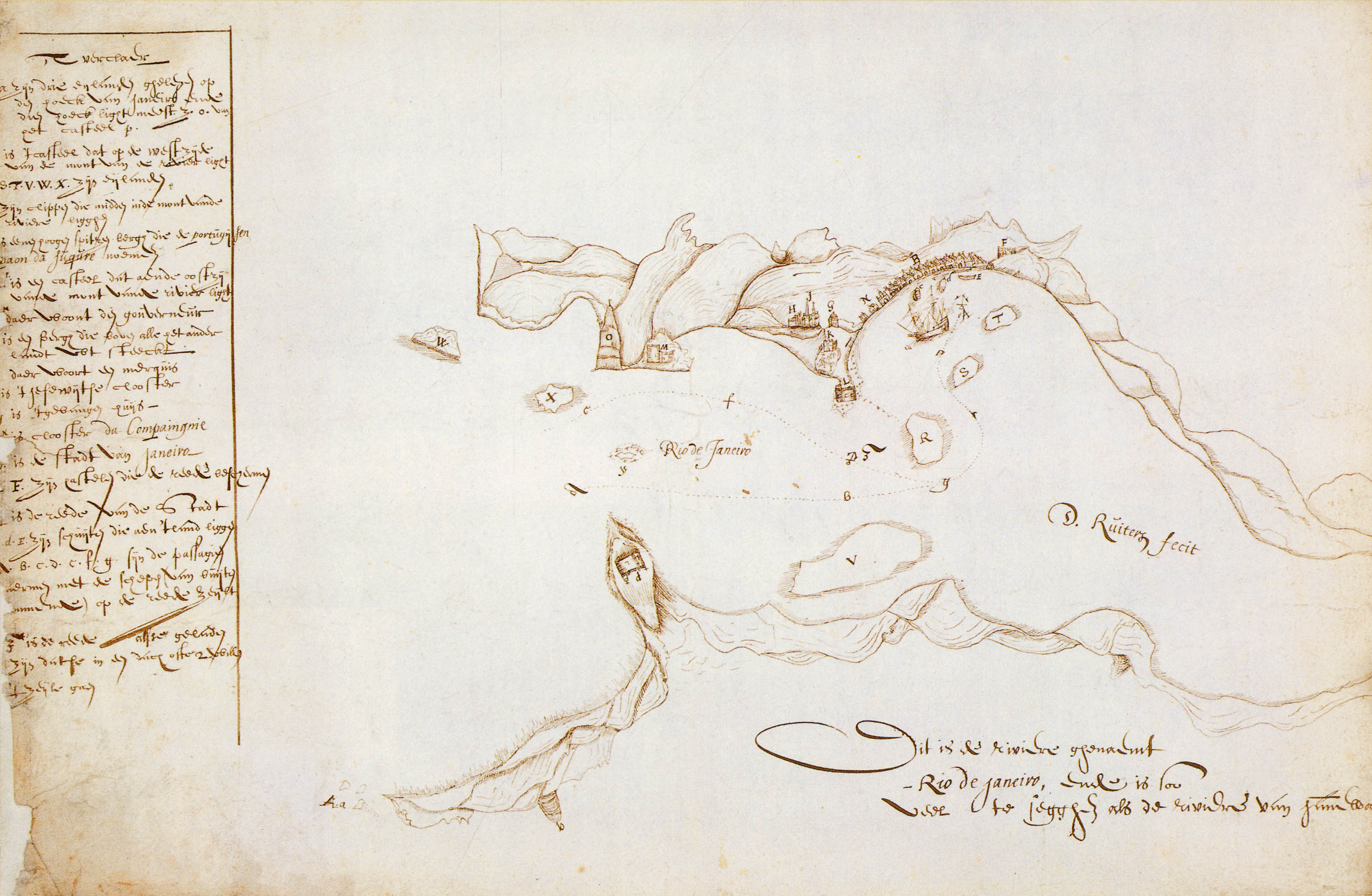

In 1619, dutch sailor created this map of Rio.

Similarly, this bird’s eye view of the Guanabara Bay by another Dutch sailor, emphasizes the importance of the lower city. The depiction of Rio de Janeiro conveys a larger and grander city, but the artist/mapmaker clearly believed the lower city to be heart of Rio. In contrast, the Morro do Castelo does not appear in any detail.

From the Legend:

Hills - Pão de Açúcar (A)

Forts - Santa Cruz (B) São João (C) Praia Vermelha (D) Villegaignon (E).

Churches - Nossa Senhora da Candelária (G), São Bento Monastery (H), S. Francisco.

Streets - (F) is the main street of the lower city

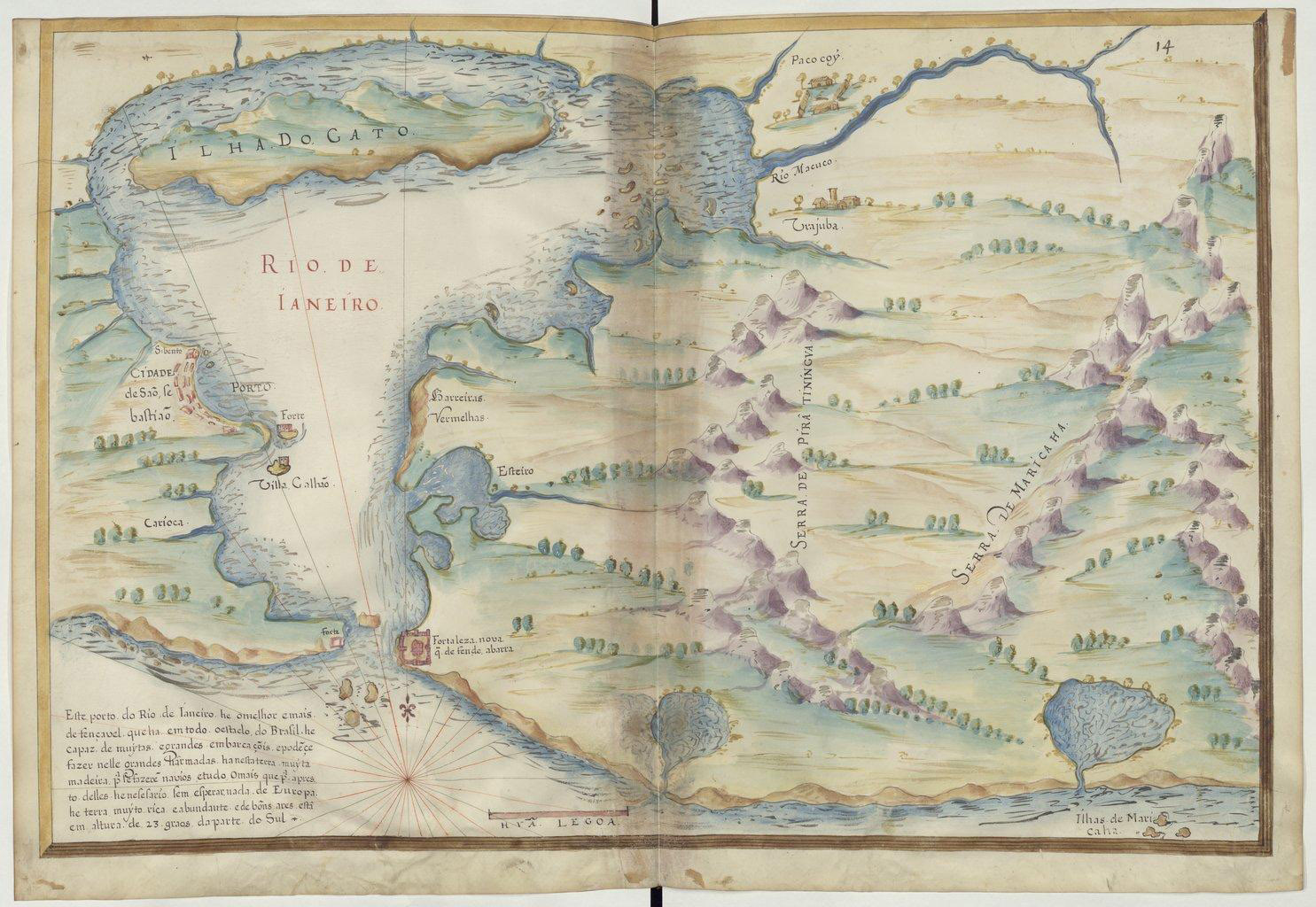

João Teixeira Albernaz’s map of the Guanabara Bay and Rio de Janeiro appeared in his hand-painted atlas of Brazil in 1627. Teixeira was the royal cosmographer to the king of Portugal and therefore had access to the best maps available. Albernaz maps the Guanabara Bay and the city of Rio de Janeiro. To the south of the city, he labels the Carioca River.

The city of Rio appears as a dry area: there are streams and rivers that empty into the bay, but not on the site of the city. Perhaps it was not his intention, nevertheless, Albernaz presents Rio de Janeiro as a dry city. On his map, he has captured one of the most pressing concerns for the residents of Rio: how to get enough water to satisfy their needs every day. The smaller rivers and springs that Albernaz paints on the map near Rio most probably were used as sources of water by those living in the city.

The legend on his map reads:

Este porto do Rio de Janeiro he o melhor e mais defençavel que ha em todo o estado do Brasil. he capaz de muytas e grandes embarcações e podemçe fazer nelle grandes harmadas. ha nesta terra mutya madeira para se fazerem navios e tudo o mais que para apresto delles he necesario. sem esperar nada de Europa. he terraq muyto rica e abundante e de bons ares esta em altura de 23 graos da parte do Sul.

[This port of Rio de Janeiro is the best and most defensible in the entire state of Brazil. It can receive many large ships and can harbor large armadas. In the land there is much timber that can be used to make ships and everything else that is necessary without needing anything from Europe. The land is very rich and abundant with good airs. It lies at 23 degrees South.]

The best source of fresh water for the lower city was the Carioca River, which emptied into the Guanabara bay along what is known today as Praia do Flamengo (Flamengo beach). João Teixeira Albernaz’s map titled "Capitania do Rio de Janeiro" from 1631 provides more detail on this water source, known as the Aguada da Carioca. The map’s legend gives the depth for the anchorage, making it clear that ships regularly stopped there to fill their water casks. For residents however, it was a long walk to the Carioca River. Residents in the city opened a trail to the Carioca River, which later became the road known as the Caminho da Carioca (Carioca Road). Possibly, water was delivered to the lower city in barrels loaded into boats that were then rowed from the Aguada da Carioca to the lower city.

From the legend:

I: Praya da Agoada dos navios della para terra espaço de 20 braças com a agoa que chamão da Carioca, onde se faz agoada, tem trezentas braças de comprido

[I: Beach where the ships take water, from the water source to the land, a distance of 20 braças, the river is called the Carioca, it is here where water is taken, it has 300 braças in length.]

Adonias, Isa. Mapa: Imagens da formação territorial brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Odebrecht, 1993.

In 1648, a recently arrived magistrate appeared before the municipal council and suggested that Rio needed an aqueduct. Wooden culverts and arches could be laid, he proposed, to conduct the waters of the Carioca River to the city. The municipal council discussed the matter and decided that it would be a right and proper service for the king to take on such a project. The municipal council then made a public proclamation to the effect that the magistrate was authorized to begin work on a Carioca aqueduct.

In 1672, the Prince Regent recognized the great need for water in the city, and authorized a small subsidy to be finances from a tax on wine. This approval, included as a copy in a document from the 18th century reveals his knowledge of the dire situation in Rio. Not only was the closest source of water one league [6.6 kilometers] away, but water was being carried from the Carioca River to the city by slaves.

Transcription:

Eu o príncipe como regente e governador dos Reinos de Portugal e Algavres, Faço saber aos que esta minha provisão virem que tendo resp. [respeito?] aos se me representou por parte do Procurador da Câmara da Cidade de S. Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro em razão de grandes inconvenientes que se seguiam ao bem comum daquela cidade de não haver agua nela para o serviço de seus moradores em menos distancia que de uma légua e causando grande trabalho a condução de se trazer à cidade por ser ás costas de escravos, pedindo-me lhe mandasse se passar provisão para que o direito de subsidio pequeno que criará para as obras da cidade se aplicasse para se conduzir a ela a agua do Rio chamado Carioca, sem que na despesa da obra que para isso se fizesse se intrometessem os governadores e visto o que alega e o que sobre a matra [matéria?] respondeu o Provedor de minha fazenda a que se deu vista. Hei por bem que o rendimento de subsidio pequeno se aplique para a dita obra sem se divertira outro algum efeito, e também a metade do rendimento das despesas da justicia? da mesma cidade porem que seja com intervenção do Governador daquela capitania Ouvidor Geral dela e do Reitor e Procurador do Colégio da Companhia de Jesus. Pelo que mando ao dito meu Governador e aos mais ministros a que tocar comprarão e guardem esta Provisão inteiramente como nela se contem a qual valera como carta . . . Paschoal de Azevedo o fez em Lisboa a 6 de maio 1672 o secretario Manuel Barreto de S. Payo o fez escrever. Principe.

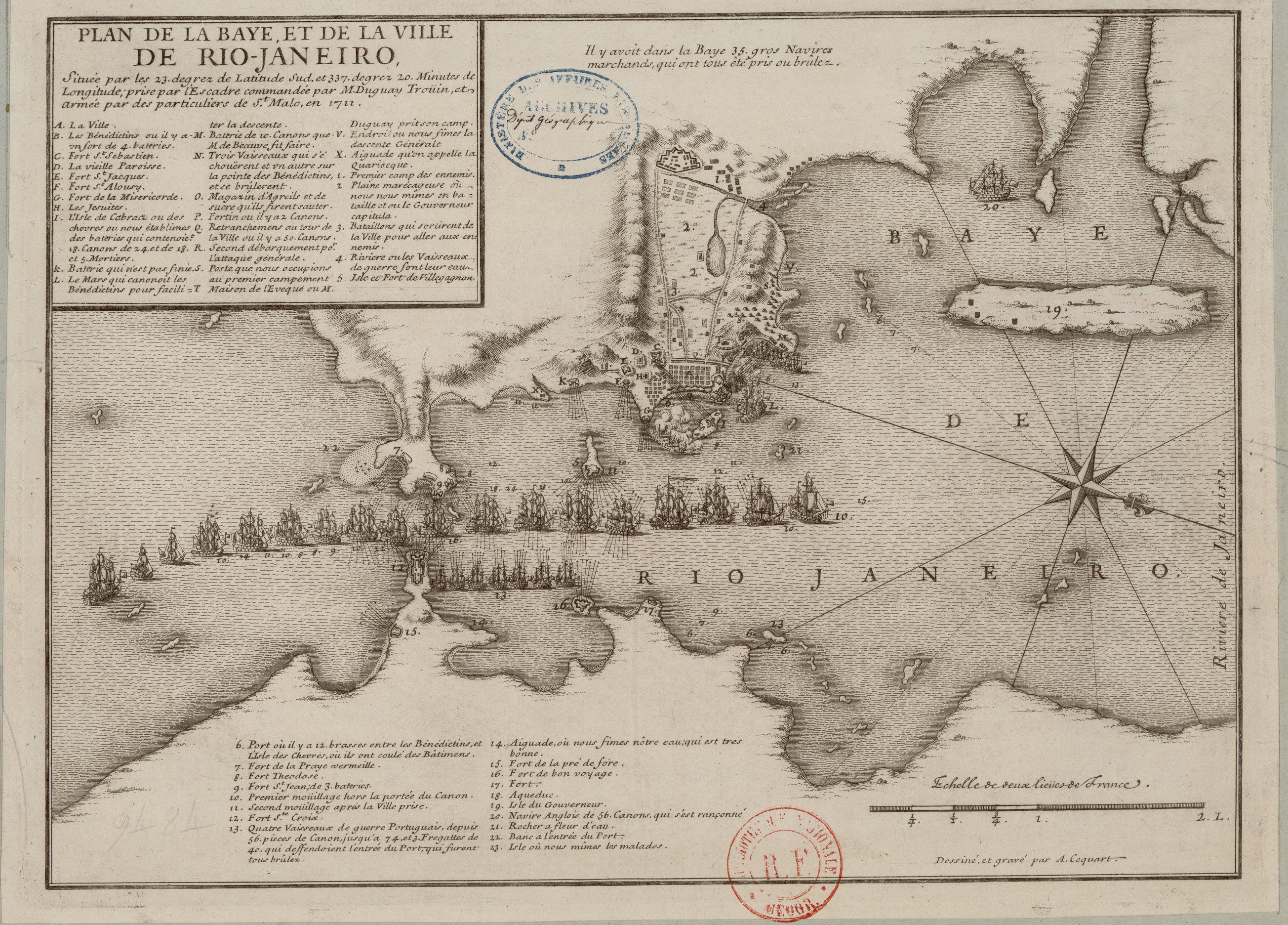

In September 1711, the French corsair René Duguay-Trouin, sailed into the Guanabara Bay, past the forts of Santo Cruz, São João, Villegagnon, and Boa Viagem and anchored next to the Ilha das Cobras, which also had a fort designed to protect the city. Overtaking this fort, Duguay-Trouin landed his men on a beach northwest of the city and then took possession of the Morro da Conceição, on top of which stood the Bishop's palace. He then began to bombard the city. A few days later, residents fled the city at night during a terrible storm. Duguay-Trouin the found himself in control of the upper and lower city and all of the ships in the harbor. Duguay-Trouin demanded a a ransom as a condition for his withdrawl, its amount, according to historian Charles Boxer included 100 chests of sugar, 610,000 cruzados in gold, and 200 head of cattle.1

This digression from the history of the Carioca Aqueduct is relevent for two reasons. First, perhaps because of its strategic importance to the French campaign against the ciy, a map made to commemorate the event (from the French perspective!) includes the aqueduct. The French mapmaker, Antoine Coquart, labels a conduit south of the city “Aqueduc.” This placement suggests that the aqueduct still did not delivere water into the lower city, but to a location still well outside. Croquart also labelled the water source where the Carioca River flowed into the bay—“Aiguade qu'on appelle la Quariocque.”

Second, the size of the ransom paid in gold offers a point of comparison when considering the eventual cost of the aqueduct. The gold for the ransom paid to Duguay-Trouin came, according to Boxer, from all gold from the mint at Rio, all of the gold that was destined for Portugal as payment for the Royal Fifth--the tax levied by the king on all gold mined in Brazil, and contributions from wealthy citizens and the governor himself. The amount in gold cruzados was 1,270,833 in reis.2

1Boxer, Golden Age of Brazil, 100.

2Boxer, Appendix VII "Portuguese Money, Weights, and Measures, 1700-1750," in Golden Age of Brazil, 354.

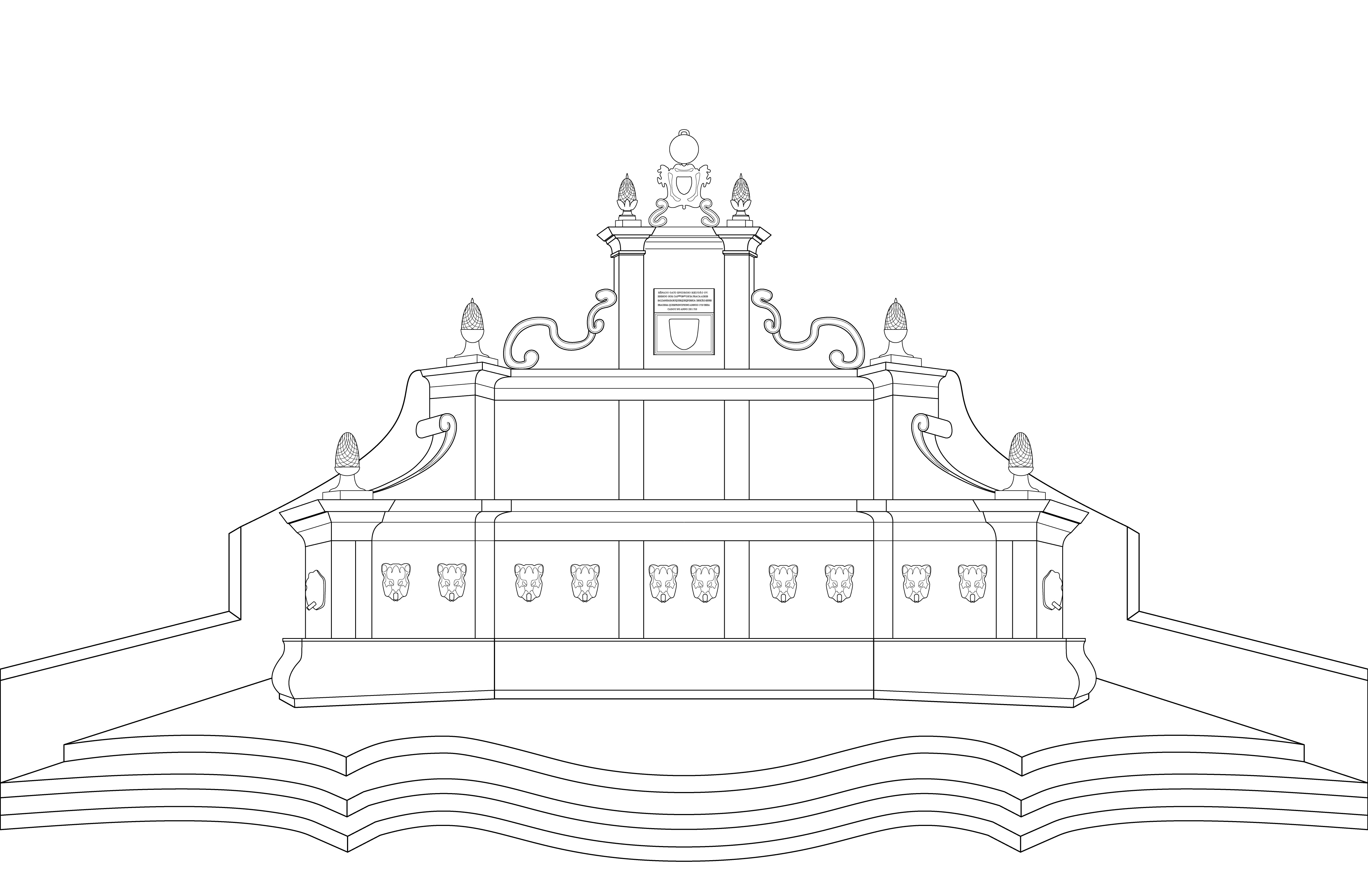

Twelve years after the devastating attack by the French on the city of Rio, the Carioca Aqueduct began to deliver water to the back of the lower city. Rio's first fountain received the water and became known as the Carioca Fountain. Designed in Portugal, the stones arrived already cut in Rio, where they were erected in the small square below the Santo António monastery.